[ad_1]

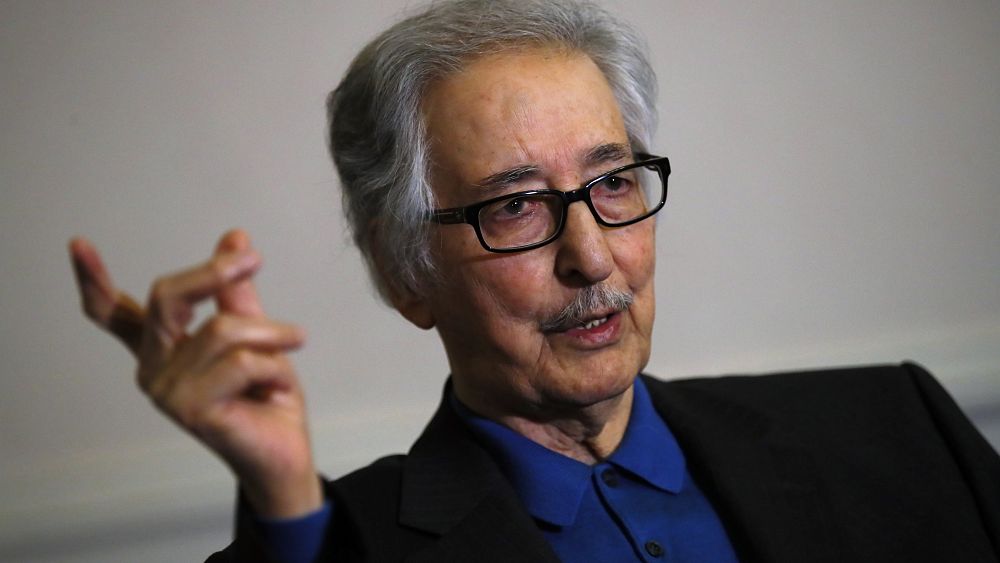

Abolhassan Banisadr, the first president of Iran after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, who fled Tehran after being charged with challenging the growing power of the clergy when the nation became a theocracy, died on Saturday.

He was 88.

Among a sea of ​​black-clad Shiite clergymen, Banisadr stood out for his western-style suits and a background so French that he confided in the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre his conviction that 15 years earlier he would be the first president of Iran.

These differences only isolated him when the nationalist tried to implement a socialist-style economy in Iran, sustained by a deep Shiite belief instilled in him by his spiritual father.

Banisadr would never cement his hold in the government he allegedly led as events far beyond his control – including the U.S. embassy hostage crisis and the invasion of Iran by Iraq – only added to the post-revolution turmoil .

True power remained firmly in the hands of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, with whom Banisadr worked in exile in France and whom he followed to Tehran in the midst of the revolution. But Khomeini would push Banisadr aside after only 16 months in office and send him back to Paris, where he would stay for decades.

“I was like a child watching my father slowly become an alcoholic,” Banisadr later said of Khomeini. “The drug was power this time.”

Banisadr’s family said in an online statement on Saturday that he had died in a Paris hospital after a long illness. Iranian state television followed suit with its own bulletin on his death. Both did not address the disease that Banisadr was facing.

Khomeini, who had previously been exiled to Iraq by Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, had to leave for France in 1978 under renewed pressure from the Iranian monarch. Once in Paris and not speaking French, it was Banisadr who initially gave the cleric a place to stay after he had pulled his own family out of their apartment to accommodate him.

Khomeini would land in Neauphle-Le-Chateau, a village outside the French capital. There, as Banisadr once told The Associated Press, he and a group of friends designed or revised the news Khomeini conveyed based on what the Iranians wanted to hear.

Tape recordings of Khomeini’s statements were sold in Europe and delivered to Iran. Other messages came out over the phone read to supporters in various Iranian cities. These messages laid the foundation for Khomeini’s return after the terminally ill Shah fled Iran in early 1979, although the cleric was unsure whether he had the support, Banisadr once said.

“It was absolutely safe for me, but not for Khomeini and not for many others in Iran,” Banisadr told the AP in 2019.

On this return, Khomeini and his Islamic Revolution swept the country. Banisadr became a member of the Cleric’s Revolutionary Council and became head of the country’s State Department on November 4, 1979, just days after the US embassy in Tehran was occupied by tough students.

In line with what was to come, Banisadr served in that capacity for just 18 days after seeking a negotiated end to the hostage situation, which Khomeini pushed aside as a hardliner.

The hostage-takers are “dictators who have created a government within a government,†Banisadr later complained.

But he stayed on the Khomeini Council and would push through the nationalization of important industries and former private companies of the Shah. And in early 1980, after Khomeini had previously decreed that no cleric should hold the newly created presidency of Iran, it was Banisadr who won three-quarters of the vote and took office.

“Our revolutionary will not win if he is not exported,” he said in his inaugural address. “We will create a new order in which disadvantaged people are not always disadvantaged.”

Amid purges by the Iranian forces, Iraq would invade the country, sparking a bloody eight year conflict between the two nations. Banisadr served as the country’s commander in chief, following a decree from Khomeini. But failures on the battlefield and complaints from Iran’s paramilitary Revolutionary Guards became a political burden on the president, who would survive even two helicopter crashes near the frontline.

A parliament controlled by hardliners under Khomeini’s rule initiated impeachment proceedings against Banisadr in June 1981 for opposing having clerics in the country’s political system, part of a long-standing feud between them. A month later, Banisadr boarded a Boeing 707 of the Iranian Air Force and fled to France with Massoud Rajavi, the leader of the left-wing militant group Mujahedeen-e-Khalq.

He came out of the flight with his signature mustache shaved. Iranian media claimed he fled dressed as a woman.

Khomeini “bears a heavy responsibility for the appalling catastrophe that has struck the country,” said Banisadr after his escape. “He largely imposed this course on our people.”

Banisadr was born on March 22, 1933 in Hamadan, Iran, and grew up in a religious family. His father, Nasrollah Banisadr, was an Ayatollah, a high-ranking Shiite clergyman who opposed the policies of the Shah’s father, Reza Shah.

“I was a revolutionary in the womb,†Banisadr once boasted.

As a teenager, he protested the Shah and was detained twice. He supported Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh, who nationalized the Iranian oil industry and was later overthrown during a CIA-backed coup in 1953. During the unrest in 1963, Banisadr suffered a wound and fled to France.

Banisadr studied economics and finance at the Sorbonne University in Paris and later taught there. He wrote books and treatises on socialism and Islam, ideas that would later guide him after joining Khomeini’s inner circle.

After Banisadr and Rajavi left Iran, they formed the National Council of Resistance of Iran. Banisadr withdrew from the council in 1984 after the Mujahedeen-e-Khalq teamed up with Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein as his war against Iran continued.

He would stay outside Paris for the rest of his life, under police surveillance, after being attacked by suspected Iranian bombers.

Banisadr rose to fame after claiming in a book, without evidence, that Ronald Reagan’s campaign worked with Iranian leaders to prevent the hostages from being released, thus foiling the re-election of then-President Jimmy Carter. This gave rise to the idea of ​​the “October Surprise†in American politics – an event deliberately timed and so powerful that it influenced an election.

US Senate investigators said later in 1992 that “the weight of the evidence is that there was no such deal”. However, after Reagan’s inauguration in 1981, U.S. arms began flowing into Iran via Israel in what came to be known as the Iran-Contra Scandal.

“The clergy used you as a tool to get rid of democratic forces,” said Banisadr in 1991 during a US tour to a former hostage. “The night you were taken hostage, I went to Khomeini and told him that he had acted against Islam, against democracy.”

[ad_2]