The death of Mahsa Amini in Iranian police custody has ignited a spark in a nation seething with anger and discontent

DUBAI: Since the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini at the hands of vice squads, protests have spread to almost all of Iran’s 31 provinces and urban cities. On September 13, Amini was arrested by a Morality Police (Gasht-e Ershad) patrol at a Tehran metro station, allegedly for violating the Islamic Republic’s strict dress code.

She was hospitalized after the arrest, fell into a coma and died three days later. Iranian authorities claim she died of a heart attack. Her family says she had no pre-existing heart problems.

Her death has sparked outrage in a country seething with anger over a long list of grievances and a host of socio-economic concerns.

Iranian women, fed up with the crudeness of the vice squad, have posted videos online of themselves cutting their hair in support of Amini. Demonstrators who took to the streets chanted “death to the vice squad” and “women, life, freedom.”

In acts of defiance, demonstrators take off their headscarves, burn them and dance in the streets. The state police cracked down on the protesters, attacking them with tear gas while Islamic Revolutionary Guard volunteers beat them. At least 41 people have died so far.

“The internet in Tehran was cut off. I haven’t been able to reach family members, but every now and then they can get a message through,” an Iranian who fled to the US during the days of the Islamic Revolution told Arab News.

Mehdi, who declined to give his full name, added: “We hope the government will make concessions this time. It was the largest demonstration since the revolution. We are proud of what is happening in Iran.”

Karim Sajdadpour, senior fellow of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, described the protests over Amin’s assassination in The Washington Post as “led by the nation’s granddaughters against the grandfathers who have ruled their country for over four decades.”

Since the Islamic Revolution in 1979, Sharia laws in the country have required women to wear headscarves and loose clothing in public. Those who do not comply with the Code are subject to fines or imprisonment.

The Iranian authorities’ campaign to urge women to dress modestly and against the “wrong” wearing of prescribed clothing began shortly after the revolution that ended an era of unrestricted fashion freedom for women under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. During the Shah’s reign, his wife Farah, who often wore Western attire, was considered a model of a modern woman.

The image of protesters destroying portraits of Iranian leaders in the northern city of Sari is just one of many that have emerged from Iran over the past week as a symbol of anti-regime sentiment. (AFP)

By 1981, women were no longer allowed to display their guns in public. In 1983, the Iranian parliament ruled that women who do not cover their hair in public could be punished with 74 lashes. The penalty of up to 60 days in prison has recently been added.

Restrictions were constantly evolving, and the degree of enforcement of women’s dress codes had varied since 1979 depending on which president was in office. The Gasht-e Ershad was formed to enforce the dress code after Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Tehran’s ultra-conservative mayor, became president in 2005.

Restrictions were eased somewhat under the presidency of Hassan Rouhani, who was considered relatively moderate. In 2017, after Rouhani accused the vice squad of aggressiveness, the leader of the force declared that women violating the vice law would no longer be arrested.

However, the rule of President Ebrahim Raisi seems to have given renewed impetus to the vice squad. In August, Raisi signed a decree to tighten enforcement of rules requiring women to wear hijabs at all times in public.

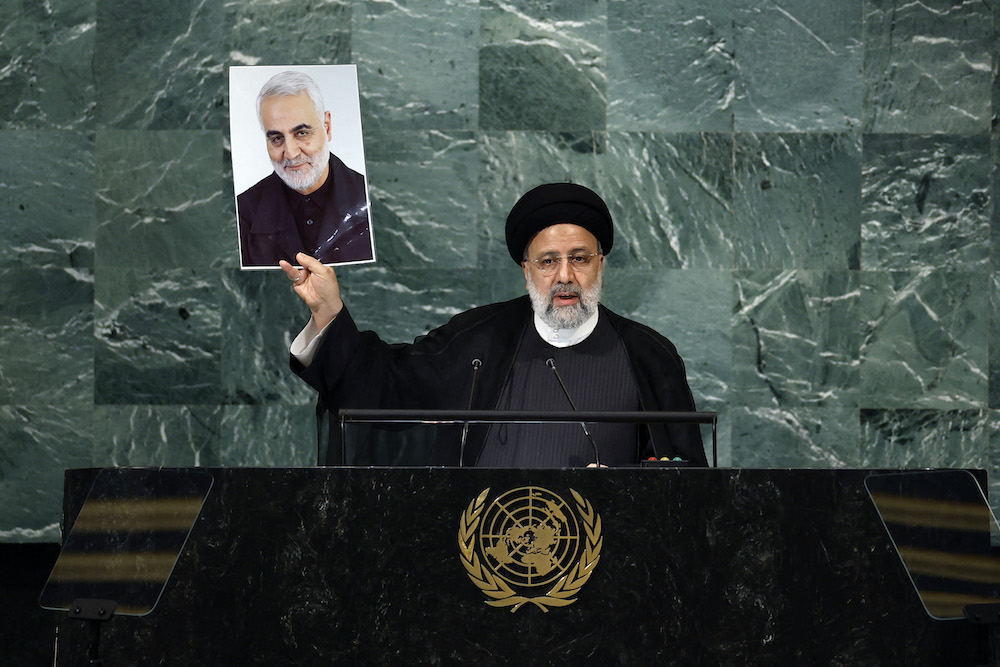

In his speech to the UN General Assembly last week, Raisi tried to deflect blame for the protests in Iran by pointing to Canada’s treatment of indigenous people and accused the West of double standards on human rights.

It gives me goosebumps to see the women taking a stand against the evil regime that has never shied away from genocide.

Mehdi, who fled to the United States during the Islamic Revolution

Raisi’s government, meanwhile, is seeking a guarantee that the lifting of severe sanctions and the resumption of business operations for Western companies cannot be disrupted if a future US president pulls out of the 2015 nuclear deal. Iranian officials also dispute the International Atomic Energy Agency’s concerns about illegal nuclear material found at three sites and want the IAEA investigation to be completed.

Be that as it may, anti-government protests in Iran are not new. In 2009, the Green Movement protested election results deemed fraudulent. In 2019 there were demonstrations over a rise in fuel prices and a deterioration in living standards and basic needs.

This year’s protests are different in that they are feminist in nature. Firuzeh Mahmoudi, executive director of United for Iran, a human rights NGO, said it was unprecedented in the country to see women taking off their hijabs en masse, setting police cars on fire and tearing down pictures of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei (the country’s supreme leader).

It’s also unprecedented to see men singing, “We will support our sisters and wives, life, freedom.”

“Through social media, mobile apps, blogs and websites, Iranian women actively participate in public discourse and exercise their civil rights,” Mahmoudi said. “Luckily for the growing women’s rights movement, the patriarchal and misogynist government has yet to figure out how to fully censor and control the internet.”

Protests over the death of Mahsa Amini have erupted across Iran and among the diaspora living around the world. (AFP)

Masih Alinejad, an Iranian political activist who has lived in exile in America since 2009, said she has received many messages from women in Iran. They have shared with her their frustrations, videos of the protests and their goodbyes to their parents, who they believe may be their last.

Explaining that she could feel her anger through her messages, Alinejad said the hijab is a way for the government to control women and therefore society, adding that “their hair and identity have been taken hostage”.

Numerous Iranian male celebrities have also expressed their support for the protests and women. Toomaj Salehi, a dissident rapper who was arrested earlier this year for his lyrics on regime change and social and political issues, released a video of himself walking the streets saying, “My tears don’t dry, it’s blood, it is anger. The end is near, history repeats itself. Fear us, retreat, know that you are done.”

For its part, the film industry released a statement on Saturday calling on the military to drop its guns and “return to the arms of the nation.”

A number of famous actresses have removed their hijab in support of the movement and the protests. Mohammad Mehdi Esmaili, Iran’s culture minister, said actresses who have expressed their support online and removed their hijab are no longer able to pursue their careers.

In a tweet on Saturday, Sajdadpour said: “To understand Iran’s protests, it is remarkable to see images of the young, modern women who have been killed in Iran over the past week (Mahsa Amini, Ghazale Chelavi, Hanane Kia, Mahsa Mogoi) , with the images of the country’s ruling elite, virtually all deeply traditional, geriatric men.”

Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi holds up a photo of Quds Force commander General Qassem Soleimani, who was killed in a US attack, during his speech at the 77th session of the United Nations General Assembly. (AFP)

The Iranian authorities have shut down mobile internet connections, disrupting the services of WhatsApp and Instagram. Speaking to Iranian state media ISNA, Communications Minister Issa Zarepour justified the law with “national security” and said it was not clear how long the lockdowns on social media platforms and WhatsApp would last as it was being implemented for “security purposes” and Discussions about current events.”

However, Mahsa Alimardani, a researcher at the Oxford Internet Institute who studies internet shutdowns and controls in Iran, said authorities are targeting these platforms because they are “lifelines of information and communication that keep the protests alive.” .

On Twitter, the hashtag #MahsaAmini has surpassed well over 30 million posts in Farsi.

“Everyone in Iran knows that the authorities will crack down on the protesters very harshly and kill them,” US-based Iranian Mehdi told Arab News.

“It’s almost target practice for them. It gives me goosebumps to see the women there standing up against the ruthless and vicious regime that has never stopped at genocide to stay in power. It takes a certain courage to do what they do.”

Looking to the future with hope, he said: “The flame is lit and we’re not the kind of people to back down.”