Hundreds of rare manuscripts from Ethiopia have been digitized online by Minnesota’s Hill Museum & Manuscript Library, shedding new light on East Africa’s contributions to Islamic and Christian school heritage.

The collection itself includes nearly 300 manuscripts from Addis Ababa University and over 500 from the Sherif Hārar City Museum in Hārar, the city where most of the items were made.

In this exclusive interview The new Arab speaks to Josh Mugler, a curator of Eastern Christian and Islamic manuscripts who worked on the project.

The new Arab: For whom is this collection being digitized and how important was it for HMML to work on this project?

Joshua Mugler: “As with all our projects, there are multiple target groups, all of which we hope will benefit.

The audience for most of our digitization projects are primarily members of the community whose heritage is being digitized, particularly in (the) diaspora. And second, scientists who study this community. Of course, these groups have significant overlap because many East African Muslims (for example) are also researching their own cultural heritage.

In the case of our Ethiopian Islamic manuscripts, I hope this work will build connections with the large community of East African Muslims here in Minnesota, primarily from Somalia. Cataloging work on these collections was started by Mohamud Mohamed, a Somali-American graduate student and native of Minneapolis who worked as an intern at HMML in 2021.

We want to make it easier for East African Muslims here and elsewhere to study these manuscripts, which are part of their own cultural history, since much has been lost through war and migration. And we want to do this in a way that doesn’t rely on removing manuscripts from the places where people have nurtured them for centuries.

This is easier to do with digital technology. This work is crucial because without cataloging there are only millions of images on a website and no one can find what interests them.”

Since the first millennium, Ethiopia has been at the heart of two manuscript book cultures, underpinning Islamic and Christian religions and administrations, and differing geopolitical realities. These Christian and Islamic manuscript cultures also developed in different languages and scripts which some scholars have argued limited our understanding of these cultures. While the historiography of Christian manuscripts is already well established, Islamic manuscripts, whether in Arabic language and script or in local languages and Arabic script (‘ağamī), have received little study.

The new Arab: Would you say that the manuscript culture of the East African region is less known than West Africa (with examples from Mali’s Timbuktu) and understudied, and how does the collection bring to light new information about what we may already know? Ethiopia’s manuscript culture?

Joshua Mugler: “Yes, I would say that East African Islamic manuscripts in particular have received less attention. Considerable attention has been paid to Ethiopian Christian manuscript culture, in part due to the microfilm work that HMML undertook in Ethiopia in the 1970s.

Given the difference in size, this is somewhat understandable: we have digitized over 700 Islamic manuscripts from Ethiopia, but we have digitized and are still working on hundreds of thousands of manuscripts from Mali alone.

So it’s a smaller community and a smaller body of material, but I look forward to making these available for research. Fortunately, there are important projects such as the “Islam in the Horn of Africa” database led by Alessandro Gori at the University of Copenhagen that are studying this region more thoroughly.”

Ethiopian Muslims began adopting literary culture and celebrating manuscript work in mosques after the advent of Islam in the seventh century. Books were stored and kept in bookshelves known as taqet, which is known as tāqat in Arabic. According to scholars such as Hassan Muhammad Kawo, these indicate that (the) African endogenous culture of preserving textual material existed before the introduction of European models for archives and museums.

The new Arab: Can you walk me through two of the pieces that struck you as the most striking or interesting, and why are they the way they are?

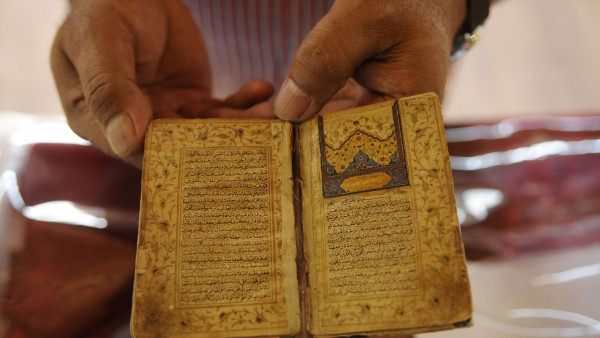

Joshua Mugler: “I was struck by the elaborate decoration of some manuscripts, especially Qur’anic manuscripts and (other) devotional books.

The style of decoration differs from that of other Islamic regions I know of, using its own local color palette (historically many reds, yellows and blacks), often with decorative white text written with negative space. See, for example, IES 00258, a 1729 Qur’an manuscript now preserved in Addis Ababa.

This type of decoration would require an investment of time and money, indicating the importance of these manuscripts. Second, I was struck by the efforts to preserve elements of Hārari and Oromo, two regional languages that are less established than Arabic in the literary tradition.

“Hundreds of Qur’anic manuscripts in these collections were copied and donated for devotional reading at the graves of family members, sometimes by men but much more often by women.”

For example, EMIP 01685 is an extensive compilation of information in Hārari from 1985, including diagrams of human anatomy and other helpful terminology. In addition, Harar has a small, centuries-old written tradition, as there are three treatises on Islamic inheritance law in the language that have been copied for almost 500 years.”

The new Arab: Has this project in any way challenged what scholars like you previously thought about manuscript culture in relation to the region?

Joshua Mugler: “I’m not an expert on Ethiopia specifically, but I know there were some surprises in these collections, such as the age of some manuscripts. The oldest dated manuscript in the collection is a work on the Ḥanafī Law copied in 1346 (EMIP 01539), which predates most previously known manuscripts in Ethiopia.

I was also struck by the role played by Hārari women in the creation and preservation of this manuscript heritage. As I further noted Twitter, Hundreds of Qur’anic manuscripts in these collections were copied and donated for devotional reading at the graves of family members, sometimes by men but much more often by women. This is a phenomenon I have not observed in other parts of the Islamic manuscript tradition.”

The new Arab: There has been much debate as to whether Ethiopian manuscripts, as Islamic and Christian, can renew the points of contact between the two. What are your thoughts on this?

Joshua Mugler: “These manuscripts bear witness to centuries of contact between Muslims and Christians in the Horn of Africa, from early contacts and conflicts in the Middle Ages to missionary activity and European imperialism in recent centuries.

Despite these contacts (both positive and negative), most of the intellectual conversations between the manuscript writers took place within the Muslim community and not across religious lines, although they otherwise interacted fairly regularly with Christians.

I think an interesting question the manuscripts raise is what it means for Hārar and the other eastern regions to be part of a multi-religious Ethiopia today. It is important for Muslims and Christians in Ethiopia to consider how to positively advance these interfaith interactions.”

Adama Munu is an award-winning journalist writing on race, black heritage and issues connecting Islam and the African diaspora