What does the headscarf controversy have to do with the 1973 Yom Kippur War? Well, the quadrupling of oil prices by the sheikhs of Araby has caused an uproar.

Posters in Arabic appeared on Oxford Street. Rooms at Dorchester and Savoy were sold out to the sheikhs who came to see the rain. The Antichrist had entered the citadel.

On the other hand, petrodollars attracted Indian workers, initially from Malabar in Kerala. These workers quickly earned enough to build Kerala’s garish “Dubai” houses that crowded a traditionally plain skyline. Since Muslims in Kerala were among the first to emerge in search of the GCC El Dorado, rancor was tinged with interfaith jealousy.

Muslims who were Muslims soon lost the edge that made them objects of anger. They outshone the more educated Hindus and Christians in clerical jobs.

The fact that non-Muslims later achieved greater success did not extinguish the initial resentment against the “Dubai House”, because the politician had now included it in his repertoire. This was a propitious time for a politician to capitalize on religious antipathy. General Zia ul Haq’s Nizam-e-Mustafa caused a stir on this side. The broad act of conversion at Meenakshipuram has fueled divisions.

At the other end in London, publishers scoured the market for books with high sellability. This is the time when especially generous advances on books were made like among the believers, by VS Naipaul (1981) and Satanic verses by Salman Rushdie (1988). Both expose Islam to satirical scrutiny.

The outsized focus on Islam, supported by the media and the book industry, gradually transformed it into Islamism. This Islamism was given a further boost by the success of the Islamic Revolution in Iran.

With Ayatullah Khomeini projecting himself as the leader of the Muslim world, deep dismay reigned in Riyadh, which saw itself as the central pole of the Islamic world. It controlled Mecca and Medina, the two holiest places.

“Control” of the holy shrines had been challenged by a dramatic occupation of the Mecca mosques by a wing of Akhwan ul Muslimeen, or the Muslim Brotherhood. This incident traumatized the Muslim world.

The occupation of the Mecca Mosque and the Islamic Revolution coincided. Both described the institution of the monarchy in Saudi Arabia as anti-Islamic. With anxious alacrity, the House of Saud proclaimed themselves “guardians of the holy shrines,” thereby dampening kingship.

Nonetheless, fierce competition erupted between Tehran and Riyadh over who would propagate the true Islam. Since one of the items on the ayatollahs’ agenda was to eliminate all traces of the fashion of North Tehran patronized by the Shah, the hijab gained a very high priority. To date, all hotels in Tehran have a plaque at the entrance urging female guests to “respect Iranian culture and wear a hijab in public places.”

The Arab mullah would not allow the ayatollahs to walk away with the trophy of Islamism and its manifestations like hijab. It’s difficult to explain to friends who haven’t traveled to Beirut, Baghdad, Cairo, or Damascus during the peaceful years of the Cold War that these cities once represented a graceful life.

Why go back so far? I was sitting with Ambassador Rajan Abhyankar, who knows Syria like the back of his hand, at a popular shawarma joint in Damascus at the start of the recent unrest when he suddenly turned and pointed to three young women wearing white hijabs. “You see, this is the result of the Iranian revolution.”

After all, Syria is the land of Comrade Michel Aflaq, the founder of Arab Ba’athism, which gained a foothold in Syria and Iraq. In their aversion to Islamic rituals, they differed little from Mustafa Kemal Pasha of Turkey a generation earlier. It turns out that the pro-Salafist thoughts of Hasan al Banna, Sayyid Qutb and Maulana Maududi clearly endured. After all, Turkey’s first lady had to fight to wear a hijab, which Kemalist culture opposed. Tayyip Erdogan is a brother in disguise (akhwan).

The rapid spread of hijab is directly related to the televised Islamophobia that broke out on the scene in 1991, the first post-Soviet expedition called Operation Desert Storm. CNN’s Peter Arnett ushered in a new era of global media from the terrace of the Al Rashied Hotel in Baghdad.

For the first time in history, a war was brought live into our salons. A television program divided the world into two opposing groups of viewers – the victorious West and the Muslim world, humiliated and angry. This continued through the post 9/11 wars and accelerated the wearing of the hijab. The Indian media followed her steps.

Rocket attacks against Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan, launched on October 18, 2001, coincided with the arrival of Narendra Modi in Ahmedabad to take over as prime minister. The Ahmedabad pogrom of 2002 took place in the shadow of American fireworks. Malice between Hindus and Muslims has coincided with rampant Islamophobia around the world.

The hijab in India tangles with the threads mentioned above, but is also an expression of stifled anger at the perceived excesses of the Hindutva towards the world’s largest minority.

The minority factor exacerbates the problem to a degree that their lordships do not seem to have noticed. The hijab protests in Iran are a confident statement by women aware of their rich heritage. Girls from Southern Canada and Udupi belong to a minority that is under unspeakable pressure.

There is no hijab problem in Pakistan or Bangladesh because the state is neither opposed nor urged to promote it.

Trust the late Khushwant Singh to get to the heart of the matter. The festive atmosphere of the Indo-Pakistani cricket match in Lahore in 2003 was enhanced by Pakistani women who appeared in stunning fashion – dark glasses, tinted hair and bright colors. The only lady in the VIP area dressed in the hijab happened to be Irfan Pathan’s mother.

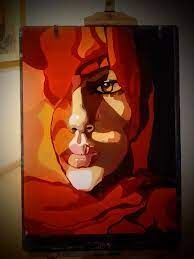

Cover Photo: Shades of a Hijab Painting by Sneha Subramanian